0 Yuan Milk Tea, 1 Trillion-Yuan Habit

Why Meituan, JD, and Taobao are fighting over more than just your next meal.

Bubble tea has always held a sacred place in my life — I literally named this entire channel Sipping VC with Boba. So when bubble tea made national headlines — not for a new brown sugar collab, but because it broke China’s internet — I had only one thought: damn, I really picked the right sector to obsess over.

On July 5th, 2025, China’s food delivery scene went wild: free milk tea — 0 yuan, zero, nothing — was everywhere.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

And what happened?

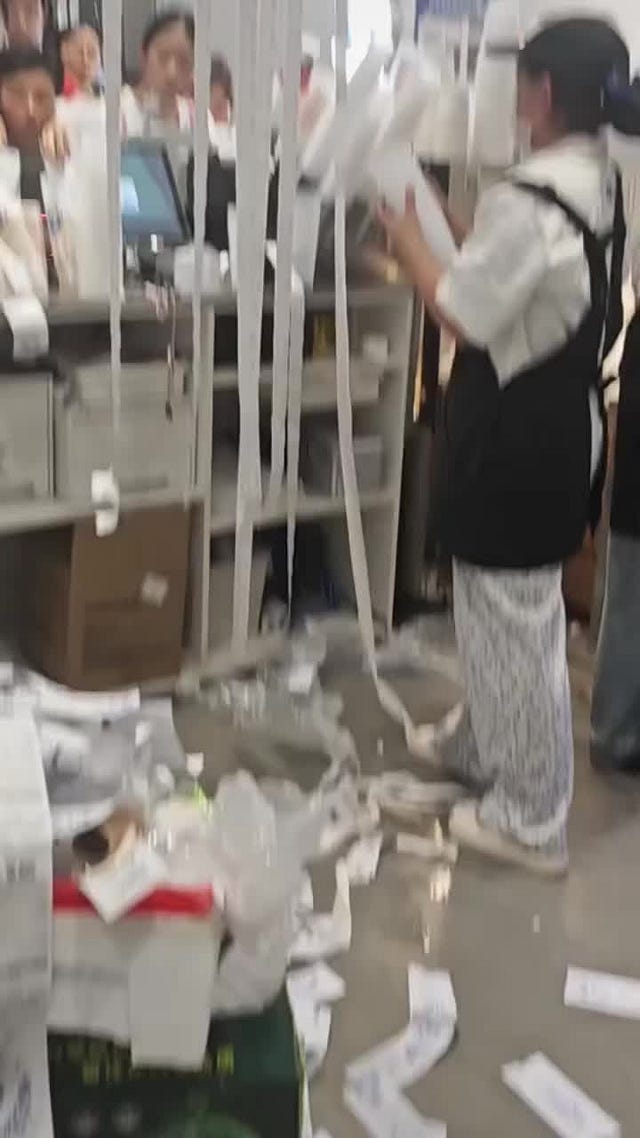

Meituan’s servers crashed.

Over 30,000 bubble tea shops couldn’t cope.

One delivery guy worked 18 hours straight, making 127 deliveries in 40°C heat.

2.2 billion food delivery orders were placed in a single day — nearly double the usual number.

For some perspective, Amazon Logistics processed 5.9 billion US delivery orders in 2023. Meituan just did 2.2 billion in a single day. Insane, right?

So what exactly are we witnessing here? A marketing stunt? A glitch in the matrix?

Not quite.

This was the opening salvo in China’s biggest platform war since the ride-hailing battles. Now, JD and Taobao — platforms historically focused on electronics and apparel — have dived headfirst into the food delivery battlefield.

Why? Surely they’re not spending hundreds of billions just to deliver lunch faster.

Of course not. They’re not fighting for takeout.

They’re fighting for your habit.

It’s not about food. It’s about frequency.

Think about how many times a day you open Taobao / Shopee / Lazada / Amazon. Once? Twice if you’re shopping?

Now think about Meituan:

Breakfast: order delivery.

Lunch: delivery again.

Afternoon: another snack or drink.

Dinner: you know the drill.

Late-night: maybe some bubble tea or a midnight snack.

That’s at least three to five times a day. And that’s Meituan’s real play. Every time you open the app, it’s another opportunity to sell you something — food, sure, but also movie tickets, hotel rooms, flights, and so on.

In the internet world, frequency = power.

This is the real game. Meituan knows that if it can get you used to ordering from them multiple times a day, they’ve got you locked in. Every time a user opens your app is a chance to sell them something.

JD and Taobao aren’t here to sell you dumplings. They’re here to win back relevance.

Because while Taobao once felt like a daily ritual, younger users now spend their screen time on Douyin or Xiaohongshu. JD knows that once you’ve opened the app for a burger, your next click could be a skincare set or a new phone.

Food delivery is just the gateway drug.

The Big Play: Instant Retail (即时零售)

During a recent trip to Beijing, I wanted to order clothes from Taobao. But I was only in town for 48 hours and had no idea if my order would arrive in time. That anxiety? That’s exactly the problem instant retail is trying to solve.

Instant retail (即时零售) is about getting anything delivered within 30 minutes.

Milk tea today. Lipstick tomorrow. A smart speaker the day after.

It’s about satisfying the need for instant gratification — the new normal.

The kind of consumer that wants everything, right now.

This is no fringe concept. The market is projected to hit RMB 1 trillion by 2026. And more importantly, it may be the last true growth market in China’s mature internet economy.

The old growth levers — getting people online, getting them smartphones, convincing them to shop on e-commerce — are maxed out. Now, the only way to grow is to change the way people consume. And instant delivery is doing just that.

Why wait two days for your parcel when you could get it within an hour?

This is how platforms are trying to reset consumer expectations — and whoever sets the default, wins.

Why they’re burning billions (and why they don’t care if you’re loyal)

So, why are these companies burning billions? Simple: scale.

In the platform economy, there’s only room for a few survivors.

The more users, the better the experience.

The better the experience, the more merchants.

The more merchants, the more users.

It’s a vicious cycle — but it’s a good one if you’re the platform on top. Platforms must acquire users at any cost, because once users are locked in, they’ll keep coming back. And once you’re in, you’ll pay that small delivery fee. It doesn’t matter. Convenience wins.

And, as history has shown, the companies willing to lose the most money in the short term are usually the ones that end up winning. Didi took over ride-hailing. Meituan wiped out its competitors in food delivery. Taobao, JD, and Pinduoduo are the e-commerce titans. Eventually, every sector becomes a duopoly or monopoly.

But here’s the catch: these users aren’t loyal. It’s a harsh truth. But that’s okay, because loyalty isn’t the goal here.

What really matters is habit. Once you’re used to having everything delivered in 30 minutes, you won’t want to wait two days for anything again.

Once that habit is ingrained, price increases won’t matter. The convenience is just too valuable. That’s when the winning platforms start monetizing the convenience they trained you to expect.

This is not just a milk tea stunt. It’s a milestone.

The 0-yuan milk tea campaign wasn’t a marketing gimmick. It was a line in the sand.

A marker for the end of China’s wild expansion era — and the start of a new phase: precision operations 精细化运营 — precision, efficiency, sustainability.

Subsidy wars will end. The tide of easy growth has receded. What’s left is real competition:

Who can operate leaner?

Who can delight customers without burning cash?

Who can create lasting value — not just temporary volume?

Like every platform battle before, this one will end with a few winners, many casualties, and a generation of consumers who didn’t realize they were being trained.

The price of that milk tea?

Not zero. Just… deferred.

🧋 Enjoyed this deep dive into China’s internet wars?

Subscribe for more essays from the messy middle of markets, tech, and identity — powered by boba, breakdowns, and just enough sarcasm to stay awake.